In the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, the defending nation of Ukraine faces a daunting challenge: to confront a larger adversary that holds significant reserves of ammunition and weaponry. Russia has sustained significant losses in ammunition and vehicles due to this war’s attrition, however, it has still yet available resources and significant offensive potential. Ukraine’s disadvantage in its stocks of war material and production capabilities has compelled it to look for ways to maximise the impact of its resources. One of the most potent assets that could aid in this effort is its arsenal of long-range strike weapons (LRS), including precision-guided missiles and UAVS capable of striking targets from a distance. These weapons offer Ukraine various strategic options, making them invaluable in Ukraine’s fight for territorial integrity and national survival.

Long-range strike weapons provide more than just tactical value on the battlefield. They enable strategic effects that extend beyond individual combat encounters by reaching critical targets behind enemy lines. The main strategic functions of LRS can be categorised into four distinct roles: counter-population, strategic interdiction, counter-leadership, and counterforce [1]. For Ukraine, each of these functions offers specific advantages against Russia, reshaping the strategic landscape in Ukraine’s favour.

Within a 300 km range, our map highlights numerous high-value targets concentrated along Russia’s western border and adjacent to Ukraine. These include critical ammo depots, such as those near Belgorod and Kursk, which are vital for supplying frontline operations. Of those available in this range, the 19th and 67th Arsenals are those which house a great number of Soviet Era Earth Covered Magazines (ECMs).

Several railway substations also fall within this range, forming essential nodes for logistics and transporting troops and supplies. Additionally, key airbases like the Shaykovka and Voronezh Malshevo house of Tu-22M3 and Su-34 respectively could be hit. Regarding oil production, at least five oil refineries in the southwestern regions of Russia are present with a combined output of 31.3 Mton/year.

Extending the range to 560 km allows for strikes deeper into Russia’s central regions, including targets such as Voronezh, Saratov, and areas near Kazan. This significantly increases the number of potential high-value sites. Due to the penetration capability of Storm Shadow missiles, ammunition depots scattered across these regions become important targets. Notably, the 68th Arsenal GRAU, located in the southwestern part of Russia, stands out as one of the largest and most modernised ammunition depots, featuring 31 new electronic countermeasures (ECMs) along with 5 Soviet-era ECMs. Additionally, the 50th Arsenal GRAU is of considerable significance due to the presence of 18 Soviet-era ECMs and a production site located adjacent to the depot.

Key airbases, such as those near Ulyanovsk, along with railway substations critical for the transportation of reinforcements and materials, become accessible. Additionally, three oil refineries, which account for an annual production of 36.3 million tons of oil, are located within this area. Moreover, logistical hubs further inland are also within reach, which could cripple Russia’s ability to sustain prolonged military operations and weaken the resilience of its energy infrastructure.

At 700 km, the range dramatically expands to cover strategic assets deep inside Russia’s interior, including areas near beyond Moscow, Yekaterinburg, and the Caspian Sea. Key examples of targets include large ammo depots around Moscow that play a vital role in supporting the central command’s military logistics, some of which are also within Storm Shadow range, but thanks to the extended range of Taurus, they could choose lower and complex flight path to avoid early detection. Important oil refineries in cities like Ufa and Yekaterinburg, along with critical airbases, provide opportunities to severely impact Russia’s energy supply and air defence capabilities. This range opens the possibility of striking Russia’s core infrastructure, destabilising supply chains and potentially influencing strategic operations far from the frontlines.

Counter-population: Deterrence through Retaliation

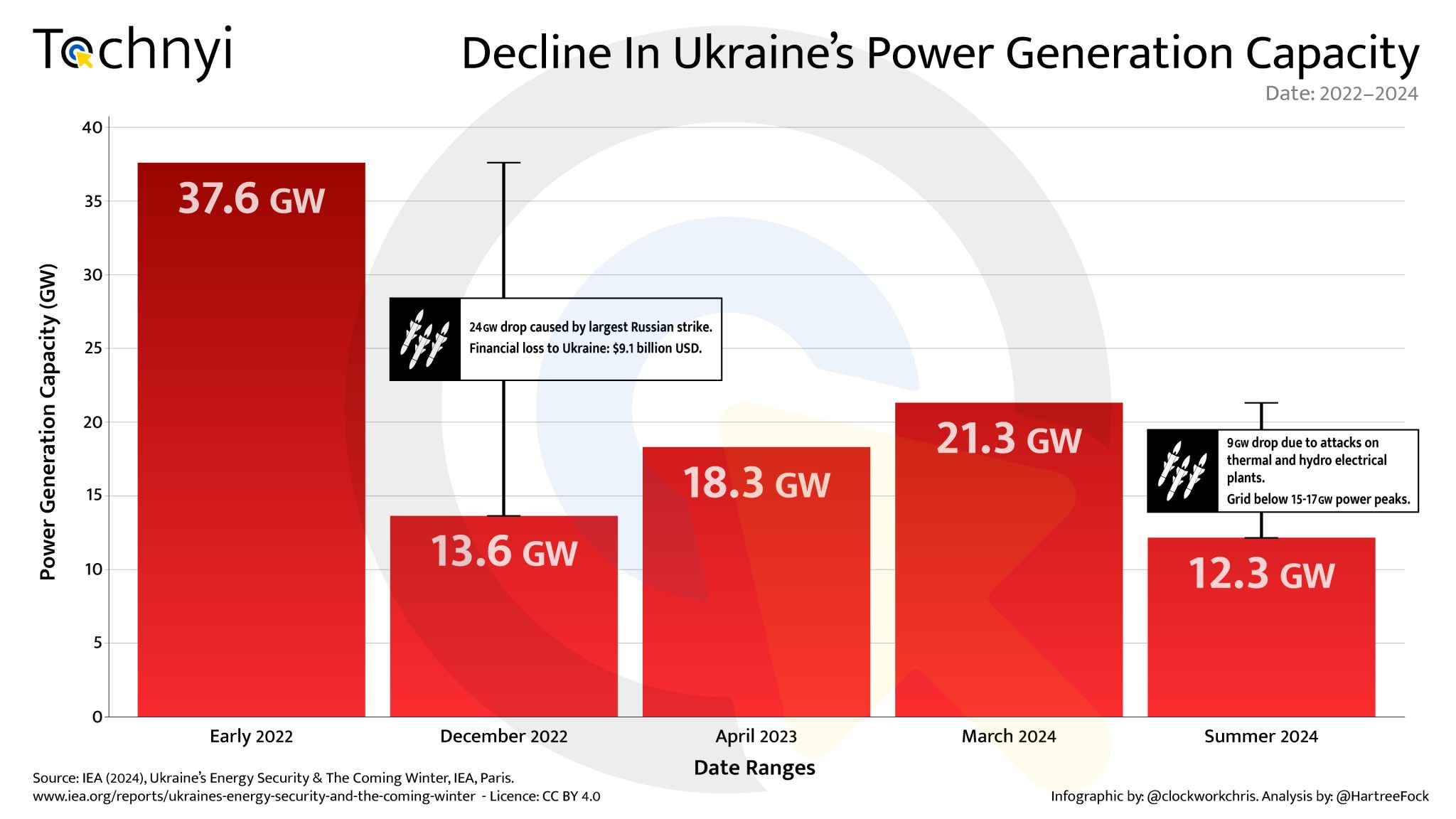

Modern warfare often targets civilian morale and infrastructure, exemplified by Russia’s attacks on Ukraine’s power grids and heating facilities. For Ukraine, enhancing long-range strike (LRS) capabilities could deter these attacks by threatening critical Russian infrastructure such as airfields, effectively demonstrating that any assault on Ukrainian civilians could lead to similar retaliation against Russia. As an example of these tactics, on August 26, 2024, Russia launched one of its largest recorded long-range strike operations against Ukraine, deploying over 200 missiles and drones, primarily targeting Ukraine’s critical energy infrastructure, causing a further loss of 9 GW in Ukraine’s power generation capability. These long-range strikes left around 8 million households without power, marking the first unscheduled blackout in Kyiv since 2022. Despite Ukraine’s air defences intercepting part of this barrage, the scale of this attack underscored Russia’s strategic focus on crippling Ukraine’s energy sector, which it has heavily targeted since its full-scale invasion in 2022. It has been estimated that the 2022 period alone, which saw the largest drop in energy generation, cost Ukraine $9 billion [2]. Notably, in 2023, the use of missiles and drones have seen a similar trend, with Shahed-136 accounting for 58% of all strikes in the second half of the year. This allows Russia to stockpile cruise missile for the campaign against electrical infrastructure.

The continued use of long-range strike weapons has severely impacted Ukraine’s power generation capabilities. Since early 2024, intensified attacks have taken down around two-thirds of Ukraine’s pre-war energy capacity. These strikes have destroyed or damaged thermal, hydro, and solar assets [3]. Even with support from international partners and Ukraine’s own proven resilience in its domestic energy supply, the approaching winter poses severe risks as the nation struggles with limited energy resources and potentially worsening power shortages anticipated. The chart reported below shows the decline in Ukraine’s power generation capacity from early 2022 to summer 2024. This chart illustrates the significant impact on energy infrastructure over time, reflecting reductions in capacity due to various factors, including long-range attacks on Ukraine’s energy assets [4]

Strategic Interdiction: Disrupting Logistics

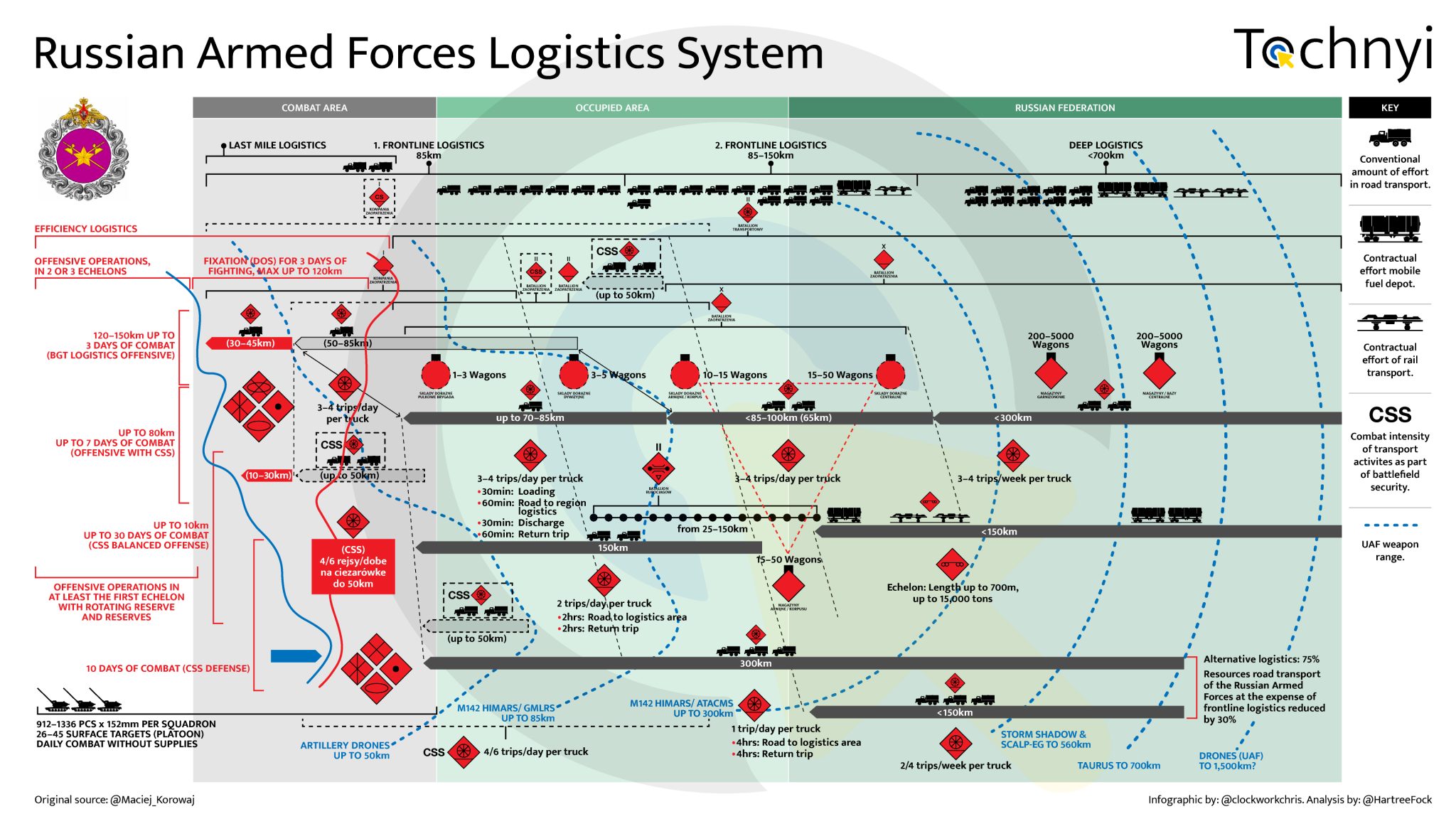

LRS can significantly impact Russian supply chains by targeting logistics routes and supply depots. With Russian forces relying on long supply lines from their territory into Ukraine, disrupting these routes would weaken their operational capabilities. Precise strikes on infrastructure far from the front lines could isolate Russian units, diminishing their morale and effectiveness, which is particularly important given Ukraine’s relatively smaller resources. To better understand why LRS are so critical on this aspect, it is important to understand how Russian logistics work at various distances from the frontline, and a good summary can be found in the image here elaborated by Tochnyi based on one posted on X by Maciej_Korowaj. This image provides a detailed view of the structure of Russian military logistics, focusing on the layered and phased resupply and transport logistics in a combat environment.

The chart outlines the Russian military’s layered logistics system, divided into frontline (0–85 km), near-front (85–150 km), and deep logistics (150–300 km) zones. Frontline logistics are highly dynamic, with supplies like ammunition and fuel delivered from CSS (Combat Service Support) hubs within 50 km. Trucks perform 3-4 daily round trips to ensure resupply for active combat units, while brigade and divisional hubs handle larger stockpiles slightly further back. This ensures a steady flow of supplies for immediate operations.

In the near-front zone (85–150 km), logistics rely on larger supply hubs supporting divisional and corps-level units. Rail and truck operations ensure the transportation of up to 50 wagons of supplies, with trucks maintaining 3–4 daily trips. Beyond 150 km, in the deep logistics zone, central storage depots [5] manage vast reserves (up to 5000 wagons). Rail networks are the backbone here, moving massive quantities of supplies via, in some cases, 700-meter-long trains carrying up to 15,000 tons. Trucks, due to the distances, operate at a reduced pace with 1–2 weekly trips. This system is designed for sustained operations, providing rapid resupply to the frontline while maintaining reserves for long-term campaigns. For defensive operations, the structure can support units for up to 10 days without external supply. Alternative logistics, like emergency routes or civilian transport, can replace up to 75% of the system’s capacity, and drones are noted for reconnaissance or limited resupply over long distances (up to 1500 km).

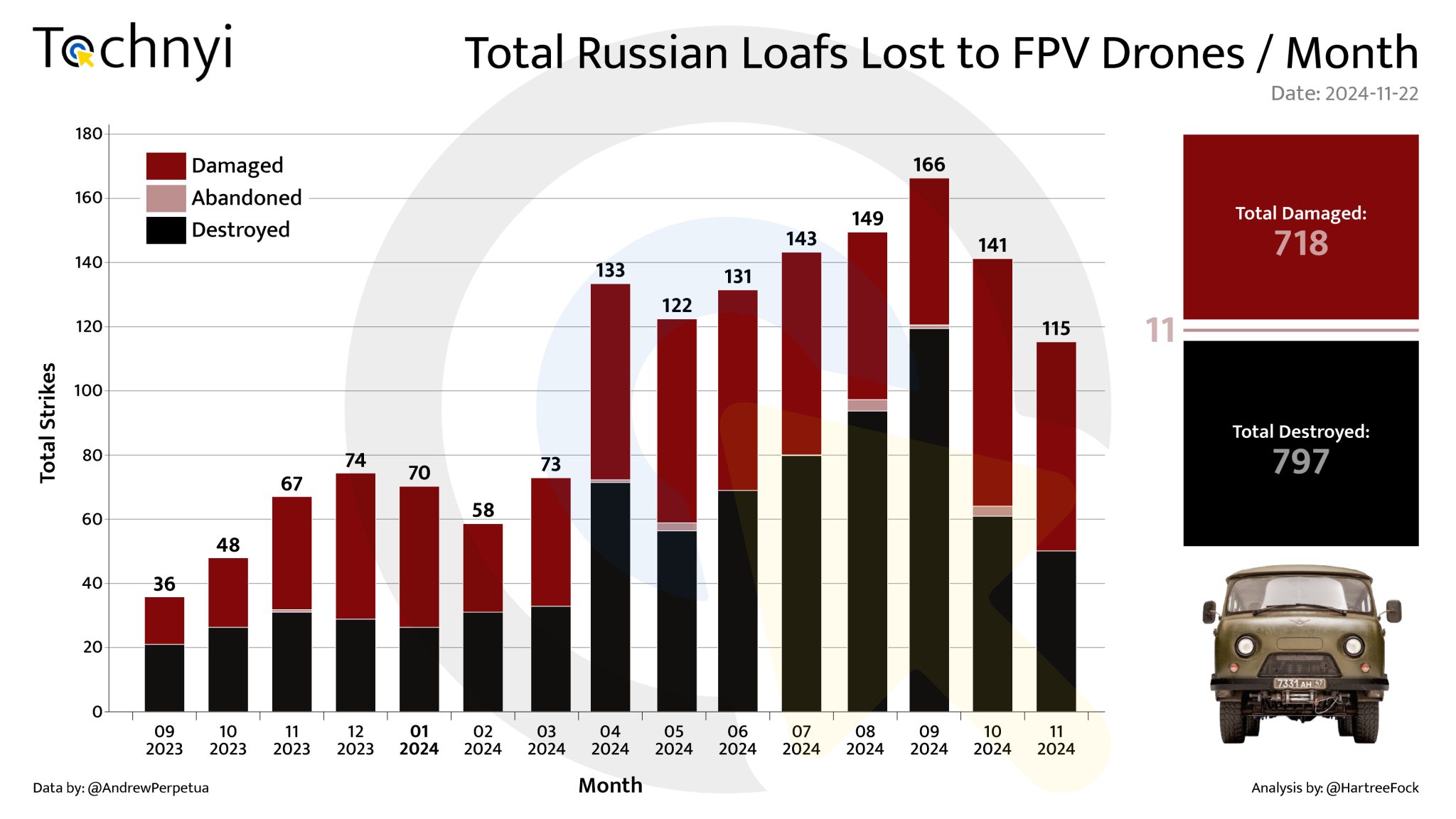

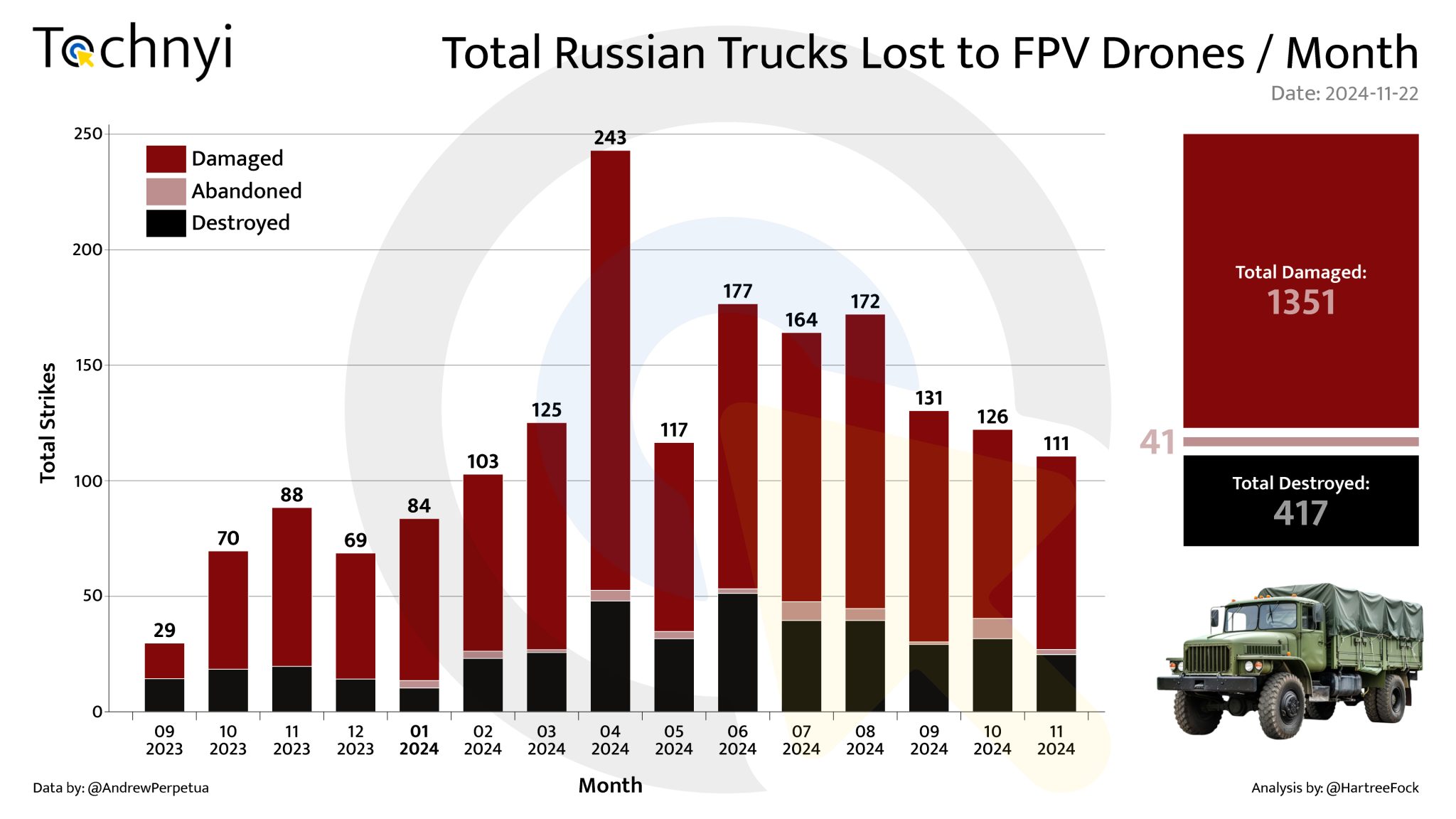

This entire system has been already put under strain by FPV (First Person View) drone strikes, which have seen a great increase in the number of observed strikes on trucks and transport vehicles such as the UAZ-452. The two graphs below show the data collected by Andrew Perpetua and his team, data which illustrates Russia’s reliance on UAZ-452, known as Loaf; an increase which potentially signals a lack of previously-staple transportation vehicles.

The ATACMS (Army TACtical Missile System), Storm Shadow/SCALP-EG and Taurus missiles are highly effective tools for disrupting Russia’s layered logistics system, particularly in the deep and near-front logistics zones. ATACMS, with a published range of up to 300 km, is ideally suited for striking critical hubs within the near-front zone (85–150 km), such as divisional supply depots, railheads, and ammunition stockpiles [6]. These strikes can sever the connection between frontline units and their deeper supply network, forcing Russian forces to rely on less efficient trucking over longer distances, which slows down resupply and weakens combat effectiveness. Storm Shadow/SCALP-EG and Taurus, with their published range of up to 560 and 700 km respectively, can go deeper, targeting central storage depots (150–300 km) and rail hubs essential for moving massive quantities of supplies. Its precision capabilities make it particularly effective against hardened or high-value targets, like command centres or fuel depots, disrupting the long-term sustainment of operations.

These missiles allow for a comprehensive degradation of Russian logistics, hitting both immediate resupply lines near the front and the deeper stockpiles that replenish them. Strikes on rail networks and depots in the deep logistics zone create cascading effects, as they disrupt the bulk transportation of supplies to near-front hubs, which then impact frontline operations. The reliance on centralized hubs and predictable supply routes makes the Russian logistics system vulnerable to these high-precision, long-range strikes. Together, they enable a layered interdiction strategy that cripples the ability to sustain operations over time, forcing Russia into a reactive posture and increasing logistical strain in prolonged engagements.

Counter-leadership: Targeting Command Structures

LRS enables Ukraine to disrupt Russian command and control by targeting military leadership hubs. Strikes on these centres could isolate commanders, slow decision-making, and create confusion among Russian forces. This approach is crucial in a centralized military structure, where the absence of leadership can lead to disorder at critical moments.

Ukrainian command alongside logistics has always kept striking command posts, and training grounds. In the early stage of the war, during the summer 2022, the use of HIMARS (HIgh Mobility Artillery Rocket System) was instrumental in reshaping Ukrainian strategy. This platform allowed a progressive degradation of the Russian supplies, to the point where holding ground was untenable, contributing to battlefield successes such as those seen in the Kharchiv and Kherson offensives. More recently, Ukrainian forces used British-supplied Storm Shadow missiles and U.S.-provided GMLRS (Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System) rockets to conduct precision strikes on three Russian command centres, targeting key military headquarters, including brigade command posts and a larger combined army unit. This operation, facilitated by advanced Western weaponry, represents a significant capability upgrade for Ukraine, allowing it to target Russian forces in occupied regions with a high level of accuracy and impact [7].

Counterforce: Engaging Military Assets at a Distance

LRS allows Ukraine to strike at Russian military assets such as artillery positions and supply hubs before their stocks reach the battlefield. Among many targets within the range of the weapon systems provided include the 120th Arsenal of GRAU. This Arsenal is known for storing different types of vehicles, from support to armored. In addition, this arsenal is a key point for artillery repair. By targeting infrastructure like this, Ukraine can diminish Russian offensive capabilities, increasing the attrition rates of Russian vehicles and ammunition, which ultimately is key to tackling the numerical disadvantages Ukraine faces. This strategy supports a proactive defence, allowing Ukraine to dictate the pace of engagement from a distance.

The pursuit of this strategy is particularly important because Russian artillery employs a broad range of artillery calibres, each tailored to specific operational roles but creating significant logistical challenges. These calibres include:

| Caliber | Examples | Typical Roles | Logistical Challenges |

| 82mm | 2B9, 2B14 | Light mortar support, infantry fire support | Portability over rough terrain, limited range and payload |

| 100mm | MT-12 | Anti-tank, direct fire support | Requires towing vehicle, limited mobility in off-road conditions |

| 120mm | 2B16 (towed), 2S9 (self-propelled) | Heavy mortar support, indirect fire, anti-fortification | Heavy ammunition, self-propelled systems require fuel and maintenance |

122mm | D-30 howitzer, 2S1 Gvozdika | Tactical fire support, portable and versatile | Widely used, but consumption strains production and supply; high demand due to versatility. |

| 152mm | 2S3 Akatsiya, 2A36 Giatsint-B | Long-range fire missions, destructive capabilities | High reliance on precise ammunition, rapid depletion of stocks, maintenance of barrels under high usage. |

| 130mm | M-46 field gun | Stopgap for long-range bombardment, older design | Limited ammunition compatibility, lower range compared to modern systems, integration issues with logistics. |

| 203mm | 2S7 Pion/Malka | High-value, destructive targeting | Limited stock and high logistical burden; specialized ammo and maintenance needs. |

| 240mm | 2S4 Tyulpan mortar | Ultra-heavy bombardment | Extremely heavy and slow; specialized ammo difficult to produce and transport. |

| 122mm (Rockets) | BM-21 Grad | Standard MLRS for volume fire | High ammunition consumption, challenging to sustain in prolonged operations. |

| 220mm (Rockets) | BM-27 Uragan | Intermediate MLRS for precision and destructive strikes | Requires specialized supply lines for ammunition; lower availability than 122mm. |

| 300mm (Rockets) | BM-30 Smerch | Long-range heavy MLRS | Heavy and advanced munitions increase cost and logistical complexity. |

The logistical challenges of supporting Russia’s diverse artillery calibers are significant. These challenges arise from the necessity to maintain multiple distinct types of ammunition across the battlefield. Each caliber, ranging from 122mm howitzers to 300mm MLRS (Multiple Launch Rocket System) rockets, requires specific production lines, storage facilities, and transportation networks, leading to a complex and often strained supply chain.

A critical consideration in the domain of artillery is ammunition compatibility, particularly within the 152mm class. While it might appear that all systems of the same caliber can share munitions, this is not the case. For example, the 2A36 Giatsint-B (towed) and 2S5 Giatsint-S (self-propelled) utilize specific types of ammunition that are not interchangeable with those used by other 152mm systems like the 2S3 Akatsiya or D-20 howitzer. This distinction arises from differences in chamber design, propellant charges, and projectile specifications, which were tailored to meet the specific operational needs of these systems (Foss, Michael. Soviet Artillery: Systems and Ammunition. London: Military Publishing, 2003).

Another aspect to highlight is the reintroduction of older artillery systems such as the D-1 (152mm) and M-30 (122mm). While these systems share calibres with more modern artillery pieces, they are fundamentally incompatible in terms of ammunition due to differences in cartridge case dimensions, propellant formulations, and projectile designs. For instance, the D-1 uses ammunition designed in the mid-20th century, which cannot be safely or effectively used in contemporary 152mm systems like the 2S19 Msta. Similarly, the M-30 (122mm) operates with ammunition that predates the standardized rounds used by systems like the 2S1 Gvozdika or D-30 howitzer (Gurov, Alexei. Ammunition and Artillery Systems of the USSR and Russia. Moscow: Defense Publications, 2015).

These compatibility issues pose significant logistical challenges, particularly in mixed-unit operations or when relying on stockpiles containing different ammunition types. Wartime conditions exacerbate these issues, resulting in bottlenecks due to high demand and limited production capacity for certain munitions. The rapid depletion of stocks in critical calibers, such as the 152mm and 203mm rounds needed for heavy artillery like the 2S7 Pion, has compelled Russia to reintroduce older systems like the 130mm M-46. However, these older systems face compatibility and operational inefficiencies and the number of barrels is limited; with a current stock estimated at around 250. Recently the 170mm M-1978 Koksan system has been seen being transported within Russia. They are likely designed as a replacement for the severely depleted long-range systems such as 2S7(M) Pion/Malka.

The logistical burden is further increased by the storage and transport requirements of larger calibers, such as 203mm and 240mm shells, which necessitate specialized handling equipment and infrastructure. Additionally, the variety of MLRS calibers (122mm, 220mm, and 300mm) complicates resupply logistics, as each caliber demands tailored supply pipelines and creates the potential for gaps in availability. These challenges can be maximised by increasing the pressure on the supply chain, increasing operational difficulties of sustaining such a diverse and resource-intensive arsenal in a prolonged high-intensity conflict.

Ukraine’s drone campaign has achieved significant results in degrading and disrupting Russian assets far beyond the frontlines; focusing on key infrastructure, logistics, and industrial targets across Russia. Recent strikes have targeted a diverse range of facilities, such as ammunition depots, oil refineries, power stations and even alcohol distilleries, severely impacting Russia’s logistical and energy capabilities. For instance, in the Bryansk region, Ukrainian drones recently destroyed a major ammunition storage facility near Karachev. This site reportedly housed extensive artillery supplies, and its destruction inflicted a critical blow to Russian munitions reserves, which are essential for sustaining the ongoing high-intensity conflict in Ukraine [8]

Ukrainian drones have also severely damaged several oil depots, including facilities in the Rostov and Kirov regions. The attack in Rostov Oblast targeted a depot where explosions led to an extensive blaze, temporarily shutting down local fuel storage capacities and requiring extensive firefighting resources. In Kirov, drones reportedly struck storage tanks at the Rosrezerv’s Zenit plant, igniting fuel tanks; highlighting Ukraine’s ability to reach Russian assets over a thousand kilometres from the Ukrainian border [9 – 10]. Additionally, Ukraine has targeted refineries and fuel infrastructure, such as the Salavatnefteorgsintez refinery in Bashkortostan. This attack, occurring roughly 1,300 km from Ukraine, marks a considerable achievement for Ukrainian forces in conducting precise, long-range strikes on Russia’s energy assets. Although Russian authorities downplayed the impact, the symbolic value of reaching such a distant target underscores Ukraine’s evolving drone capabilities.

Between January and June 2024, Ukraine conducted an intensive campaign targeting Russian oil facilities, with 36 recorded strikes aimed at disrupting Russia’s refining capacity. This campaign reportedly [11] reduced Russian oil refining by over 15% during this period, emphasising Ukraine’s ability to carry out deep strikes far from its borders. Targets included major refineries crucial for supplying domestic fuel and supporting military logistics. The strikes highlighted Ukraine’s use of domestically produced drones, which provided both a cost-effective and strategic advantage. Ukraine’s rationale for these operations extended beyond tactical damage. By hitting critical infrastructure, the campaign sought to weaken Russia’s military fuel supply chains and impose financial burdens which led to a ban on the export of gasoline [12], which followed the import of fuel from Belarus and Kazakhstan [13, 14] showcasing a strategic effort to hinder Russian war efforts [15].

Despite these successes, the overall impact remains debated. While some sources suggest that refinery production recovered relatively quickly after repairs, the cumulative cost of disruptions and repairs for Russia was significant and the sanctions imposed by the West had a role in delaying the purchase of parts and components [16]. Estimates indicated losses of approximately $135 million per month due to altered production and export dynamics. [17] Recent updates from Reuters indicate that at least three large refineries have had to cut their processing capacity by half, with some reducing production by more than 50%. Increasing economic pressures are pushing some toward bankruptcy. This situation, combined with a significant drop in global prices and the impact of sanctions, has further weakened the Russian petrochemical industry [18].

Conclusions

The case for providing Ukraine with long-range strike weapons like ATACMS, Storm Shadow/SCLAP-EG and potentially Taurus is not merely of tactical importance but strategic, combating multiple dimensions of the ongoing conflict. These weapons allow Ukraine to offset its numerical and resource disadvantages by targeting critical infrastructure, logistics, and command structures deep within Russian-controlled territory. By disrupting supply lines, degrading enemy leadership and command capabilities and impeding military operations far from the front lines, LRS can reshape the battlefield dynamics in Ukraine’s favor.

Moreover, such weapons are essential in countering Russia’s strategy of attritional warfare, which has relied heavily on its ability to sustain operations through robust logistics and industrial capacities. Ukraine’s success in leveraging drones and precision-guided munitions to weaken Russian infrastructure and supply chains has already demonstrated the potential of long-range capabilities on imposing significant costs on the aggressor. Expanding these efforts with advanced systems could further erode Russia’s ability to wage war, forcing it to divert resources and adapt to a reactive posture.

While Ukrainian drones have proven effective in striking Russian assets, they are inherently limited in their destructive capacity, survivability, and payload, which constrains their strategic impact. The limitations of drones are evident in terms of both range and payload. Ukrainian drones can strike key targets, but they lack the heavy warheads necessary to inflict substantial damage on fortified infrastructure or larger military complexes. To achieve deeper and more impactful strikes, Ukraine would benefit from advanced long-range missile systems like ATACMS, Storm Shadow/SCLAP-EG and Taurus cruise missiles, which offer greater precision, range, and explosive power than drones. However, these advanced Western-provided systems have come with restrictions that prohibit their extensive use inside Russian territory, limiting Ukraine’s ability to fully leverage its capabilities in the broader conflict.

The argument that long-range strike weapons are not of meaningful use is misguided and often originates from a misunderstanding of their role, particularly when viewed through the lens of U.S. military doctrine, which tends to emphasize the massive use of such weapons in the preparatory phase of broader combat operations. This perception overlooks the situational nature of LRS advantages, which are highly dependent on evolving battlefield realities.